The Teesta River water sharing issue has loomed large over India-Bangladesh relations for over a decade. Hereby, analysing the issue in detail.

What are the salient features of Teesta River?

The Teesta River originates from the Pauhunri Glacier, Teesta Kangse near Khangchung within the Eastern Himalayas, Sikkim of India.

From the Pauhunri Glacier (a great snow peak in the Himalayas), the Teesta finds its way through the Darjeeling ridgein a narrow and deep gorge with a meandering course.

Teesta then runs downhill through Sikkim and Darjeeling hills for 172kms, then meanders along the plains of West Bengal for about 98kms and eventually enters Bangladesh where it flows into River Brahmaputra at Fulchori.

What is the importance of Teesta River?

The Teesta originates in the Indian state of Sikkim and its total length is 414 km, out of which 151 km lie in Sikkim, 142 kms flow along the Sikkim-West Bengal boundary and through West Bengal, and 121 km run in Bangladesh.

In Bangladesh, the River mainly affects the five northern districts of Rangpur Division: Gaibandha, Kurigram, Lalmonirhat, Nilphamari and Rangpur. According to a report on the Teesta by The Asia Foundation in 2013, its flood plain covers about 14% of the total cropped area of Bangladesh and provides direct livelihood opportunities to approximately 7.3% of its population.

For West Bengal, Teesta is equally important, considered the lifeline of half-a-dozen districts in North Bengal.

How River sharing is impacting relation of India and Bangladesh?

India as both upper & lower riparian state has come into conflict with most of its neighbours on the issue of cross- border River sharing.

In spite of sharing 54 Rivers, India & Bangladesh have an agreement in place only for sharing of oneRiver, the Ganges signed in 1996.

This treaty rather than diffusing the water conflict has only heightened the perceived neglect of Bangladesh as a lower riparian state due to large scale desertification of areas of north west Bangladesh due to reduced discharge available at Farraka Barrage. The aim of construction of the Farakka Barrage was to increase the lean period flow of the Bhagirathi-Hooghly branch of Ganga to increase the water depth at the Kolkota port which was threatened by siltation. This is due to over drawl by the states of Uttar Pradesh & Bihar as these upper riparian states were not included as part of the treaty. Thus, lack of internal water sharing agreement for Ganges River has resulted not only in threatening the survival of the Kolkata port, it has also caused straining of relations between India & Bangladesh.

The Bangladesh government feels that the reduction in flow caused damage to agriculture, industry and ecology in the basin in Bangladesh. Because of the inability of the concerned governments to come to any lasting agreement over the last few decades on sharing the River water, this problem has grown and now it is also viewed as a case of upstream-downstream dispute.

Even though UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, 1997 attempts to resolve such issues amongst riparian states, as India & Bangladesh are non-signatories to this convention, the issue of distribution of water & its management is straining Indo-Bangladesh relations despite Indian attempts at reviving the relationship with Bangladesh to a new level of trust & cooperation.

What are the other water related disputes?

Construction of the Tipaimukh Dam is another contentious issue between India and Bangladesh. Tipaimukh Dam is a hydel power project proposed on the river Barak in Manipur. Bangladesh’s objection is that it would have adverse ecological effects in its eastern Sylhet district. In spite of India’s reiteration that no dam would be constructed overlooking Bangladesh’s objections, the controversy is far from over.

The popular arguments in Bangladesh against the Tipaimukh project are:

- India should not decide what is good for people of Bangladesh without taking them into confidence;

- No study has been undertaken in Bangladesh to assess the impact of the ecosystems that exist and depend on the natural flow of the water in Surma-Kusiyara-Meghna and their tributaries.India and Bangladesh have agreed on a joint study group to examine the points raised by Bangladesh.

How the Teesta river dispute originated?

Historically, the root of the disputes over the River can be located in the report of the Boundary Commission (BC), which was set up in 1947 under Sir Cyril Radcliffe to demarcate the boundary line between West Bengal (India) and East Bengal (Pakistan, then Bangladesh from 1971). In its report submitted to the BC, the All India Muslim League demanded the Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri districts on the grounds that they are the catchment areas of Teesta River system. It was thought that by having the two districts, the then and future hydro projects over the RiverTeesta in those regions would serve the interests of the Muslim-majority areas of East Bengal. Members of the Indian National Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha opposed this. Both, in their respective reports, established India’s claim over the two districts. In the final declaration, which took into account the demographic composition of the region, administrative considerations and ‘other factors’ (railways, waterways and communication systems), the BC gave a major part of the Teesta’s catchment area to India.

After the liberation of East Pakistan and birth of a sovereign Bangladesh in 1971, India and Bangladesh began discussing their transboundary water issues. In 1972, the India-Bangladesh Joint Rivers Commission was established.

What is the present agreement related to Teesta?

In 1983, an ad hoc arrangement on sharing of waters from the Teesta was made, according to which Bangladesh got 36% and India 39% of the waters, while the remaining 25% remained unallocated.

A lesser share for Bangladesh takes into account a groundwater recharge that takes place between the two barrages on the Teesta — at Gazaldoba in Jalpaiguri on the Indian side and at Dalia in Lalmonirhat in Bangladesh. The remaining 25 per cent was left unallocated for a later decision. Especially because the regular flow of a small quantity of water (in the case of the Teesta, 450 cu secs) is imperative for the life of a river.

What are the salient features of the 2011 agreement?

Delhi and Dhaka reached another agreement — an interim arrangement for 15 years — where India would get 42.5 per cent and Bangladesh, 37.5 per cent of the Teesta’s waters during the dry season. The deal also included the setting up of a joint hydrological observation station to gather accurate data for the future. However, the deal was rejected by the West Bengal Chief Minister. Mamata Banerjee is of the view that the water-sharing would be against the interest of West Bengal farmers and people. She feels that the loss of higher volume of water to the lower riparian would cause problems in the northern region of State, especially during drier months.

What is the role of state in Water Sharing Agreement?

Although Article 253 of the Indian constitution gives power to the Union government to enter into any transboundary river water-related treaty with a riparian state, the Centre cannot do it arbitrarily without taking into consideration the social, political and economic impact of such a treaty in the catchment area.

Further foreign policy is a central subject in India. The states do not have jurisdiction in determining India’s external relations. That is an area to be handled exclusively by the government at the centre. But given the steady rise of regional parties and the increasing dependence of governments in New Delhi on their state allies, the impact is being felt in the area of foreign policy as well.

What are the present issues?

The present issue related to Teesta River is due to the formation of hydroelectricity dams.

- The rapid development of hydropower projects in Sikkim, and indeed in large parts of the northeast has been a growing cause of concern in India.

- The region has witnessed an increasing number of landslides. The reduced flow of the river particularly in the lean season has made performing river related rites difficult.

- The concerns center on the social and environmental impacts of run of the river projects that reroute the river through tunnels, bypassing long stretches of the natural river course.

- The dams upstream on the Teesta and its tributaries in Sikkim are creating a substantial reduction in water flow downstream, owing to periodic landslides, siltation, etc., notwithstanding the fact that these dams do not provide for water storage.

- Siltation has been a major problem, with projected capacities decreasing at alarming rates, often before the entire project is completed. Evaporation from the reservoirs and seepage of water from canals deprived the marginal land of the command area from the water that it was assured during the planning of the project. The dams that were designed to moderate floods have created floods by releasing.

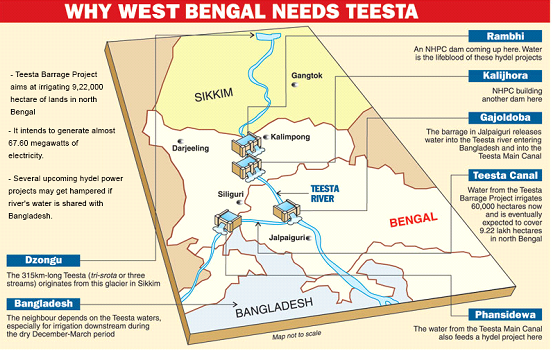

- Furthermore, the Teesta Barrage Project (TBP) at Gajoldoba in Jalpaiguri district of Bengal constructed at a cost of more than Rs. 1300 crore may be deemed as anotherde facto bottleneck in the resolution of the water sharing process. The TBP was conceived as a multi-purpose project in the aftermath of the massive floods in Jalpaiguri in 1968. This was done in an over-ambitious manner for flood control, power generation and irrigation of more than nine lakh hectares of command area in north Bengal. While TBP has contributed to flood control to an extent, particularly downstream of Sevoke (near Siliguri) where the river descends to the flood plains, there has been much less success towards increasing the areas under irrigation in the lower command area, apart from reducing the down-stream flows to Bangladesh. The operation of TBP and water diversion through the Teesta-Mahananda irrigation canal has changed the hydrological character of Teesta River south of Gajoldoba. These developments have contributed to a decline in the area occupied by the active river by more than 50 per cent during the 1991-2014 period. All these developments have had their consequences on the water flow to Bangladesh.

What should be the future course?

Water is a key resource that sustains life on planet earth and a critical element for human beings for their survival, healthy life, entertainment and social and economic development. With population growth and ever expanding urbanization and industrialization resulted in the ever increasing imbalance between water availability and water demand. More than a billion people are living in areas of physical scarcity, and half a billion people are approaching similar situation.

An easy resolution may not be feasible under the hydrological conditions prevailing at present. Unless an integrated view of Teesta basin management is adopted, the water and power needs of Sikkim and Bengal cannot be attended to in juxtaposition to the needs of Bangladesh in the Rangpur command area. A comprehensive river basin management approach is a sine qua non for optimum gains, not only for both India and Bangladesh, but also for the riparian regions and states along the Teesta.